WINTER 2009_The End of The World And Other Bedtime Stories

_ARCTIC CIRCLE

Projects

- Data Fossils by Tobias Jewson

- Data Geologies by Tobias Jewson

- Scatterbrain: A Cautionary Tale by Jack Self

We sit in wait for the end of the world. We have always regaled ourselves with unnerving tales of a day yet to come. Tomorrow is a dark place and our culture is full of tales of a natural world out of control. Whether it be nuclear apocalypse, viral epidemic, tumbling asteroids or eco catastrophe our anxieties about our future demise chronicle the flaws and frailties of the everyday.

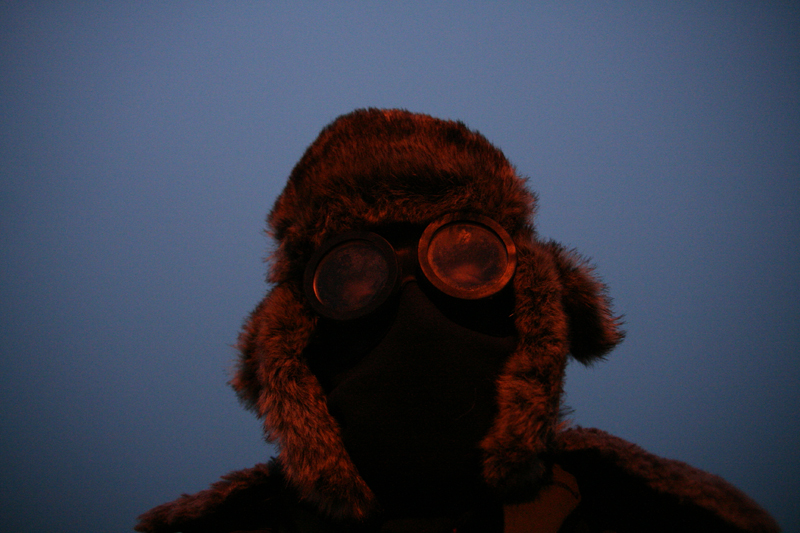

We have recruited a vagabond troupe of doomsday cultists to join us in this world after the crash; to dance in the shadow of catastrophe and question our fears and misgivings about the future. We have breathed life into the characters and actions of our UNKNOWN FIELDS DIVISION and we have armed ourselves with the props and paraphernalia to survive in the new world.

Together we have voyaged to the edge of the world, ‘the last wilderness’ of the arctic. We pilgrimaged to visit the glaciers before they melt and we shed a tear under the electric skies of the aurora. We have not gone quietly into the night but instead in the arctic we have forged an intentional community and cult compound of activist architectures, eco terrorist responses and maverick manifestos.

09/10 Division Roster

Leaders: Liam Young and Kate Davies

Researchers: Ioana Iliesiu, Georges Massoud, Antonis Papamichael, Tobias Jewson, Seung-Youb Lee, Harri Williams-Jones, Jihyun Heo, Quiddale O’sullivan, Jack Self.

![]()

Data Fossils by Tobias Jewson

Unknown Fields Data Archaeology Lab_Winter 2009_Arctic Circle 3°57’48.1″N 17°23’23.1″W

In the Unknown Fields Divisions Data Archaeology Lab Tobias Jewson and Ioana Iliesu have explored what happens to our collective history when everything is digital. In the digital era our information no longer takes the form of the physical, but that of a electronic file stored in ‘the cloud’. Our collective history is quickly effaced from this fragile and ephemeral domain, a computer crashes, formats are quickly obsolete, a hard drive is lost and all is gone. With our attachment to physical objects and mementos becoming increasingly superseded by our relationship to information, what will we leave for future generations?

The project employs design speculation as a critical tool to explore the potential ways in which architecture and landscape may respond to our ever evolving digital fascination. ‘Data Fossils’ has evolved as a series of fictional scenarios grounded in technically rigorous physical and computational investigations. Real techniques have been developed for encoding digital information in the physical world at both individual and collective scales.

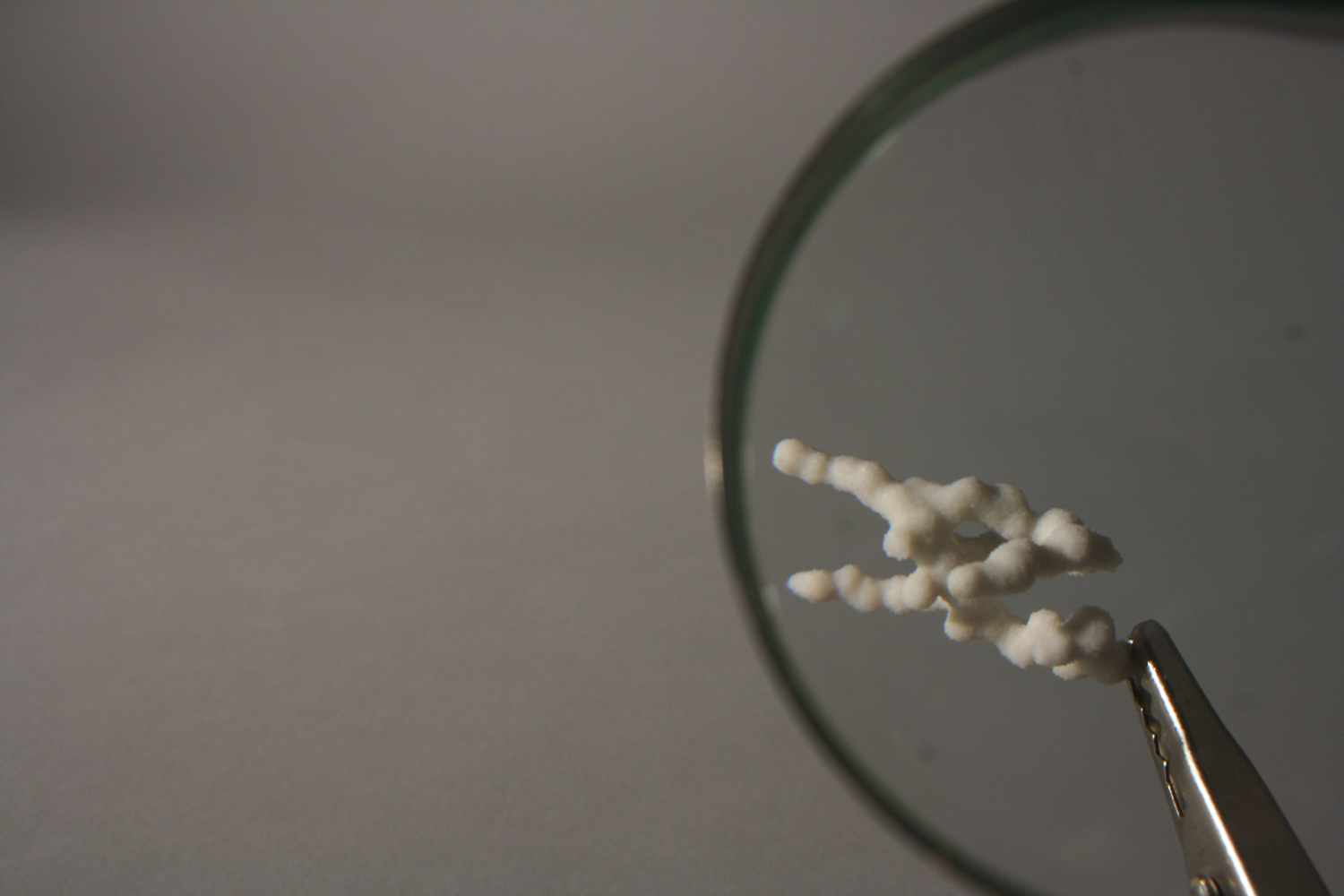

Advances in biocomputing are allowing the possibility of storing data in living, physical forms. As the division between our bodies and the digital becomes increasingly blurred, the bone’s ability to remodel itself, in response to stress, can be hacked to provide data storage. Polyps of calcified binary code become written onto our skeleton, recounting our digital identities.

A teenage informational glutton comes for a surgery consult, his skin stretched with the growths of excessive music and porn downloads. His hoarded browser bookmarks cripple his every movement.

A poet’s finest sonnet is read like Braille through his skin, prostitutes steal the secrets of their bussness clients through gentle carresses of their naked body.

The treasured remains of a loved one becomes an archaeology of memories.

An illegal immigrant hacks and grafts fragments of data bone into his own body in an attempt to conceal his true identity. His airport xray scan reveals the extensive titanium grafts typical of data identity theft.

![]()

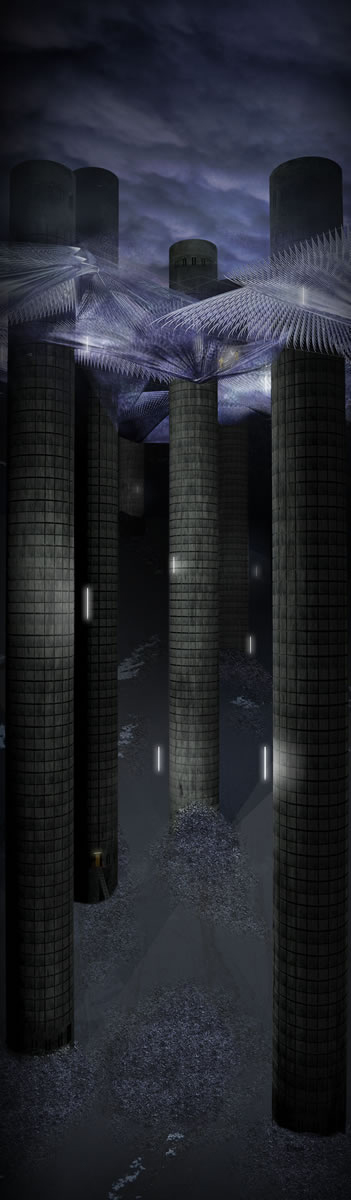

Data Geologies by Tobias Jewson

Unknown Fields Data Archaeology Lab_Winter 2009_Arctic Circle 3°57’48.1″N 17°23’23.1″W

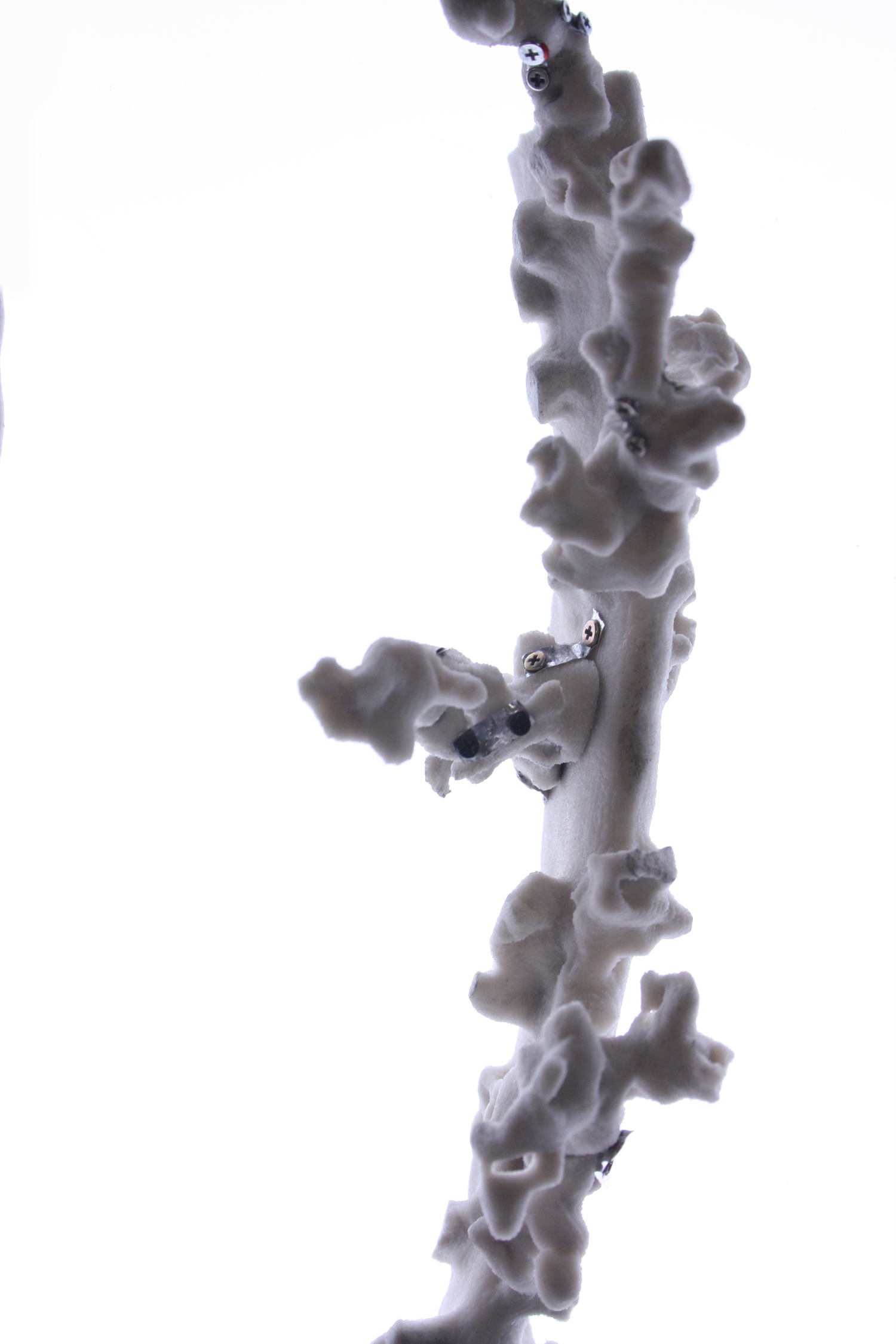

In the Unknown Fields Data Archaeology Lab Tobias Jewson has evolved his data fossils experiments from the intimate and personal attachments that calcify on our own bones into a vast digital geology of an internet archive cast into layers of volcanic glass across Iceland’s deserts. In the digital era our information no longer takes the form of the physical, but that of a electronic file stored in ‘the cloud’. Our collective history is quickly effaced from this fragile and ephemeral domain, a computer crashes, formats are quickly obsolete, a hard drive is lost and all is gone. With our attachment to physical objects and mementos becoming increasingly superseded by our relationship to information, what will we leave for future generations?

Our collective history can be deposited in columns and strata of earth – where once archivists trawled the library stacks, data geologists now roam the Icelandic landscape. Like climate records trapped in ice cores data archiving can also become a geological process. In southern Iceland the division found a ravaged landscape of eroding lava deserts- a desolate crust hiding beneath it extraordinary geothermal resources that now support huge investments in an emerging national industry of data storage and server farms. Data Geologies rehabilitate this damaged landscape by co opting these investments in technology and reimaging the Icelandic typology of data archives.

A suite of new software applications that subvert existing digital prototyping machines to encode the ephemera of the digital world into ever evolving architectural landscapes. Hoards of machines traverse the lava deserts, scraping loose sand from the surface, and under immense heat transforming it into elaborate glass like geometries, within which our recent internet activities are encased. Programs are developed to encode data inputs into structural building elements.

Simulation software is developed for the realtime growth of data geology from live twitter streams.

Informational topographies grow based and cluster on keyword inputs. The drugs keyword feed is especially active from late evening to early morning.

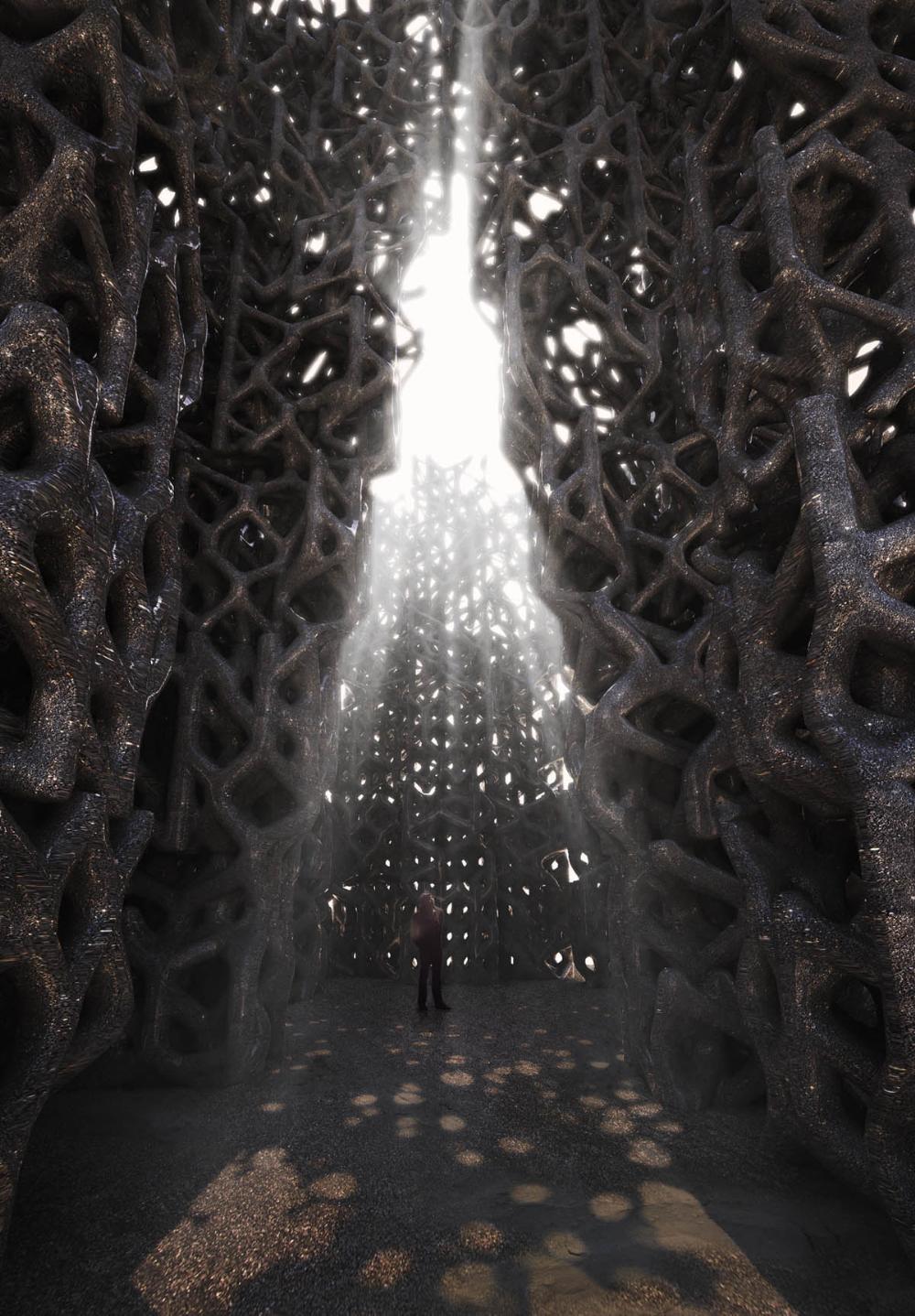

Topsoil blown by the harsh arctic winds soon gathers in the lee side of these immense structures, the grounded geological layer sprouting grass and moss. Over time, habitats will grow in the glimmering hollows as fields of data slowly reverse Icelandic soil erosion. Local Islanders read the growth of this landscape from afar, whilst archaeologists look close ,using advanced MRI scanners, searching for insights into our past. Information enthusiasts scan google earth sattelite images, deciphering geographies of data from across the globe.

People pilgrimage to this area known to hold the last data relating to flurry of internet activity from the day Michael Jackson died. It becomes an informational cathedral, a spatial obituary grown from a real time data feed.

And while tourists might flock to see history in the making archaeologists will read the dull fragments of frozen silica as records of our digital pasts.

![]()

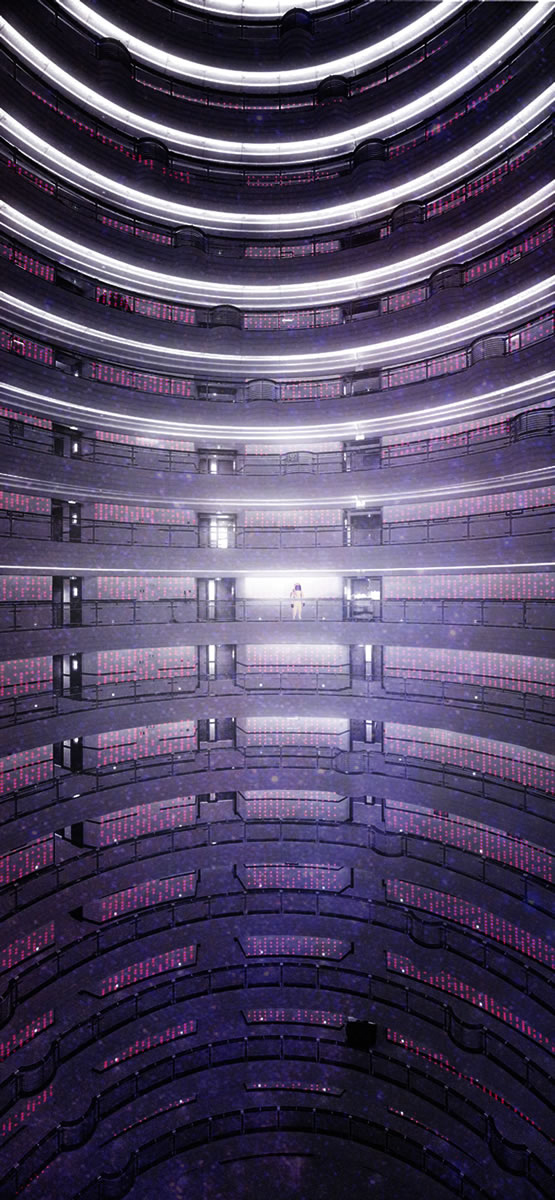

Scatterbrain: A Cautionary Tale by Jack Self

Unknown FIelds Department of Intangible technologies_Winter 2009_Arctic Circle 63°57’48.1″N 17°23’23.1″W

Scatterbrain Iceland is an architectural novella that proposes, through a narrative format, the construction of the Internet as an artefact, as a supercomputer server-farm. This is an excerpt:

“A crest of purple reflection wavered along the length of Songling’s bodysuit as her arm described the perfect parabola required to deliver the grenade to its target. As her hand attained the apogee of its circuit her front foot sunk into the spongy bundles of fibre-optics, which splayed under her shifting weight. Beneath her boots the crystal canopy quivered and flexed, and beneath that the halos of solid-state drives chimed like miniature bells in an informatic cathedral. The grenade now twisted along its arc, moving silently through the hibernal gloom across the fantastic billow of blue and red LEDs, across the floating sea of rhythmically pulsing information.

Fifty yards away the ventilation shutters of a server tower chattered and clicked, broadcasting thermal semaphore to electric storm clouds. A square hole in the curving basalt façade marked the liminal space leading to an open service hatch. As the grenade cleared the threshold of this short tunnel two yellow-suited figures appeared, Guardians of the Cloud. They each held a cordless neon tube powered by the immense electromagnetic field of the thousands of servers that filled the tower. The Guardian closest to the doorway also held a weapon, the barrel of which was already rising as he came into view. The vectors of these bodies – the grenade and the Guardian – shared an interstice both in time and space. Bouncing off the Guardian’s shoulder, the grenade would continue a new trajectory past the lift head, down the central column of the tower. It would pass eighty storeys of concentric server cores and detonate – immediately the ventilation shutters would snap closed, disrupting the chimney-effect that regulated the Web’s temperature. The immense heat generated by the computers would build up under the stack. Very soon the whole tower would combust, quickly setting fire to its neighbours.

But Songling would not live to see this. The fulcrum of the two bodies was precisely the same moment that the Guardian’s trigger-finger achieved critical pressure. The force of the bullet striking Songling’s shoulder caused her to turn as she fell, revealing a spinning panorama of towers, a landscape of computational infrastructure that extended out beyond the geothermal reactors to the limits of the valley. This was the New Internet, a machine that did much more than simply recollect the virtual lives of humanity. It inter-compared, analysed, synthesised, and generated abstractions. It constructed elaborate logical underpinnings and formulated its own languages to test the structure and consistency of our world. It had become an organism.

It produced idiosyncratically inconsistent and unpredictable opinions, like its creators. But what only Songling seemed to comprehend was that the Internet would not accept this grossly parasitic relationship with its parents for much longer. For obvious reasons, the Web could not be allowed to survive.”